- Higher Education

- K12

- Professional

- Pricing

- Resources

-

-

-

CONTENT TYPE

-

-

-

NEW FEATURE

-

-

-

-

- Login

- Global

- CONTACT SALES EXPLORE GOREACT

Higher Education

What’s Inside

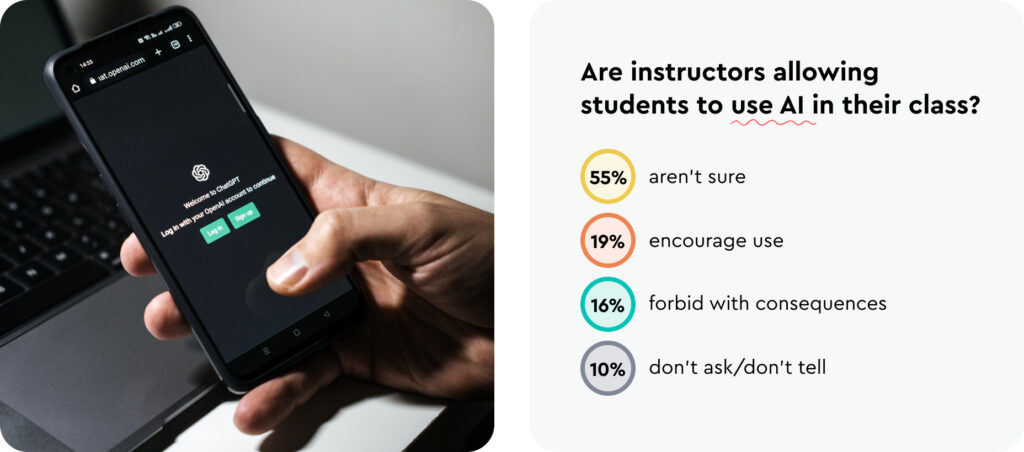

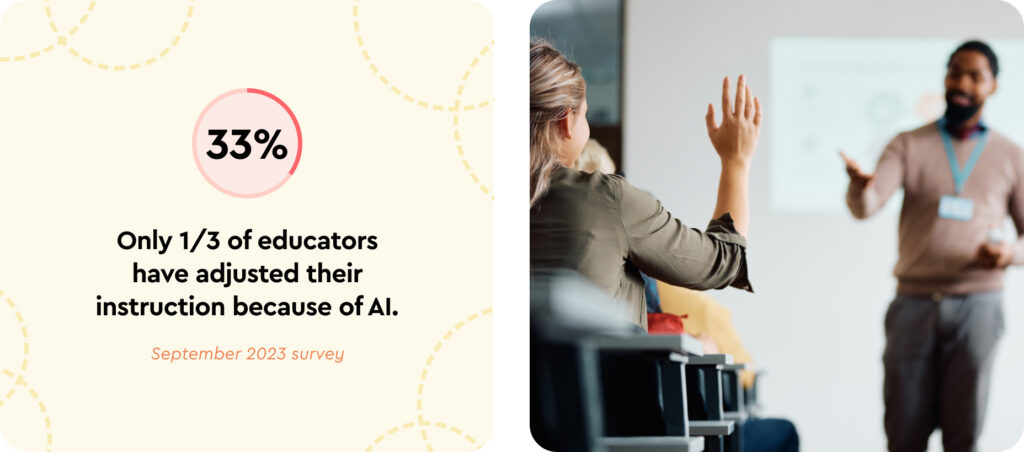

Like it or not, Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools such as ChatGPT are here to stay, and are certain to gain in popularity and capability over the coming years. Higher education administrators and professors are currently taking drastically different approaches to the problem, while many haven’t yet made up their minds as to the proper course of action.

Our aim here is to:

Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools such as ChatGPT have exploded in popularity and are being used to create content and resources (including video) for social media, marketing, research, customer service, software development, and unfortunately, higher learning. The days of asking a friend to help you write your term paper are over, since ChatGPT can produce term papers, research papers, essays, poems, biographical profiles, presentations, research summaries, short stories, video scripts, and more, all in a few minutes.

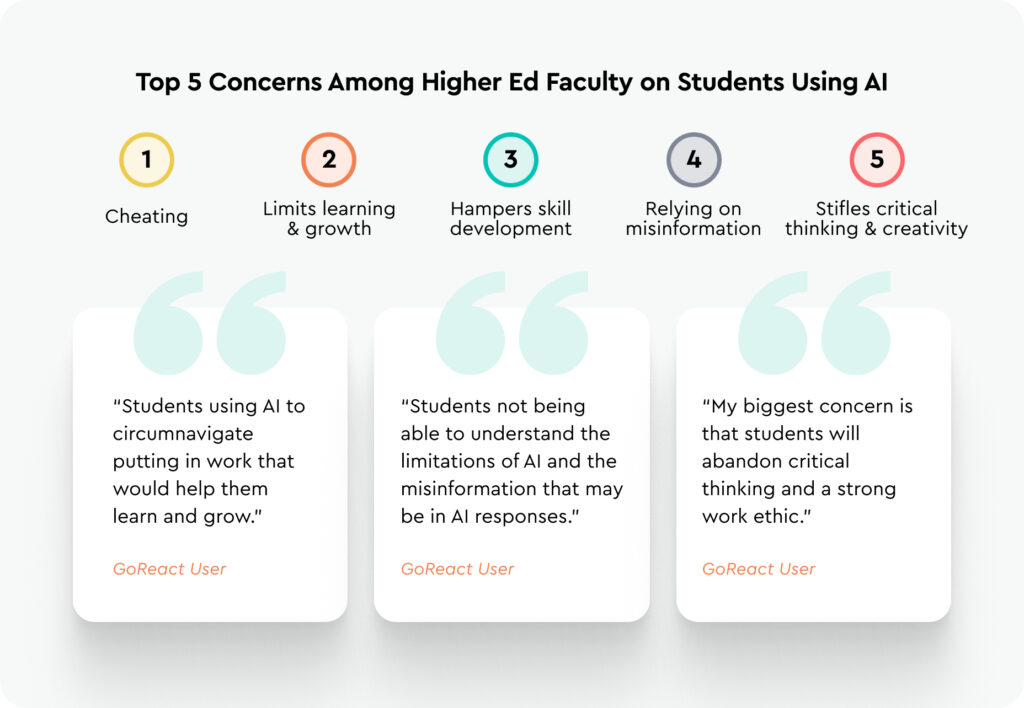

As a result, education researchers are finding that using AI simply to create content short-circuits meaningful learning. Students who use AI tools without proactive monitoring and feedback by teachers are not learning the skills they need to thrive in today’s workplace.

In an effort to fight the problem, many professors and higher-learning institutions either adopt a zero-tolerance approach and ban the use of AI tools altogether, relying on unreliable AI-detection software to expose plagiarism, or they may insist on handwritten assessments in an effort to bypass potential AI use. Neither of these approaches is practical nor is it likely to be effective, as we’ll see below.

Traditional assessment methods include fill-in-the-blank tests, multiple-choice quizzes, essay questions, and similar assessment tools. These types of assessments are staples of our current education system, primarily because they are easy to grade. However, while these types of assessments can provide a snapshot of the student’s mastery of a particular subject’s key facts at a specific time, they don’t don’t fully evaluate how well students will be able to apply their knowledge to what they’ll be doing after graduation. Anyone who has gone through traditional higher education will attest that it’s common to “cram” for exams, simply memorizing the required facts or figures, shortly before a test, regurgitating them during the exam, and then quickly forgetting them after the exams are over.

Overall, while traditional assessments might be easier to score, they don’t fully allow students to demonstrate what they have learned. This limits students’ ability to develop and display higher-level, real-world skills such as critical thinking, communication, collaboration, problem-solving, leadership, conflict resolution, and giving presentations. According to the NACE Job Outlook Study, 57% of employers feel that recent graduates are not proficient in these skills. Unfortunately, adding AI-generated content to a traditional assessment strategy makes things even worse.

Jenny Gordon, VP of International Markets at GoReact, points out, “We are at a crucial juncture in education and job training. At the moment we know that a lot of the existing roles that we need to train people for are critically underfilled, and that there aren’t enough people who can do the jobs at the right standards. So, we are educating a lot of people, but not necessarily in the right things or in the right way. Additionally, we are in this interesting sort of ‘limbo’ space where we’re not really sure what students need to be trained on for the future. Yet, for various reasons, we’re still training them and assessing them in very traditional ways—through essays, for example—rather than through practical, authentic assessment.”

So, what can educators do? What’s needed is a move away from traditional assessment methods toward more authentic assessment strategies.

Authentic assessment evaluates students using person-to-person activities such as presentations, collaborations, feedback sessions, video interviews, speeches, co-teaching, debates, slideshows, and anything that requires them to apply their knowledge and skills to real-world scenarios, rather than simply memorizing a set of facts for a traditional quiz or test. Ideally, authentic assessment helps students learn new material and apply it over an extended period of time in valuable ways, rather than simply “cramming” and regurgitating (and then forgetting) information one time for a quiz or test. The goal of these assessments is to show how well a student can apply what they learn in the classroom to real scenarios, by mirroring real-life tasks and skills that they will use in the workforce, rather than simply completing a traditional writing assignment, quiz, or exam.

Educate students on “how to learn” rather than just absorbing knowledge:

An authentic assessment strategy will take more effort on the part of administrators and professors, despite its value. This can obviously result in some push-back from apprehensive professors and administrators. However, even in cases where traditional assessment methods are used and administrators or professors are reluctant to fully buy in to the increased time and effort needed for authentic assessment, dramatic improvements can be made with very little modification to the traditional assessment.

Dr. Derek Bruff reveals which assessments are most vulnerable to AI intervention:

Traditional assessment methods such as handwritten, in-person essays may still be utilized in some situations, ideally combined with more authentic assessment methods such as question-and-answer sessions or instructor feedback/response. However, with the growth of remote learning and the increased digitization of all communication, handwritten quizzes and examinations are often viewed as old-fashioned. Hand-written entrance essays today may, of course, be merely hand-transcribed versions of AI-generated content. This brings us to the problem of AI-generators versus AI-detectors.

Vice reports that in January 2023, NYU professors specifically banned the use of ChatGPT, included the prohibition in the “academic integrity” sections of their syllabuses, and many gave their students an explicit verbal warning on the first day of class not to use the AI tool to cheat on assignments. One professor specified that any use of ChatGPT or other AI tools that generate text or content constitutes plagiarism.

Some institutions and professors are making changes such as requiring handwritten assignments rather than typed/word-processed ones, effectively taking a technological step backward a couple of decades. This is neither practical nor desirable in many cases, however.

Even before AI-generated text was possible, many secondary and tertiary learning institutions had been using software to examine written content for plagiarized or improperly cited passages. Today, professors may be required to use multiple tools, including AI-enabled resources, in an effort to not only crack down on old-school plagiarism but the new AI-generated content. The logical conclusion of this approach is effectively an arms race between AI text generators, AI-detectors, AI-detector-detectors or countermeasures, and so forth, where authentic assessment and creative thought become secondary to the battle between AI software superpowers.

Furthermore, Jesse McCrosky, a data scientist with the Mozilla Foundation, warns of AI text detection tools’ limitations, emphasizing that no method of detecting AI-written text is foolproof. This effectively makes them useless in facilitating authentic assessment, says McCrosky. “Detector tools will always be imperfect, which makes them nearly useless for most applications… One can not accuse a student of using AI to write their essay based on the output of a detector tool that you know has a 10% chance of giving a false positive.”

According to McCrosky and other critics of AI-detectors, since AI tools are continually improving, and it will always be possible for software to create text with the specific intent of evading these AI-content detectors, it’s not practical to use them. “There will never be a situation in which detectors can be trusted,” says McCrosky.

While NYU has (for now) aligned with the strictly anti-AI position, other institutions disagree, reasoning that the AI genie is fully out of the bottle, so it’s more productive and realistic to deal with the problem pragmatically. One approach some higher-education professors are taking is to not only allow ChatGPT, but require students to use it.

NPR reports on Ethan Mollick, associate professor teaching classes on entrepreneurship and innovation at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, and one professor who has recently started requiring students to use ChatGPT in his classes. “The truth is, I probably couldn’t have stopped them even if I didn’t require it,” Mollick says.

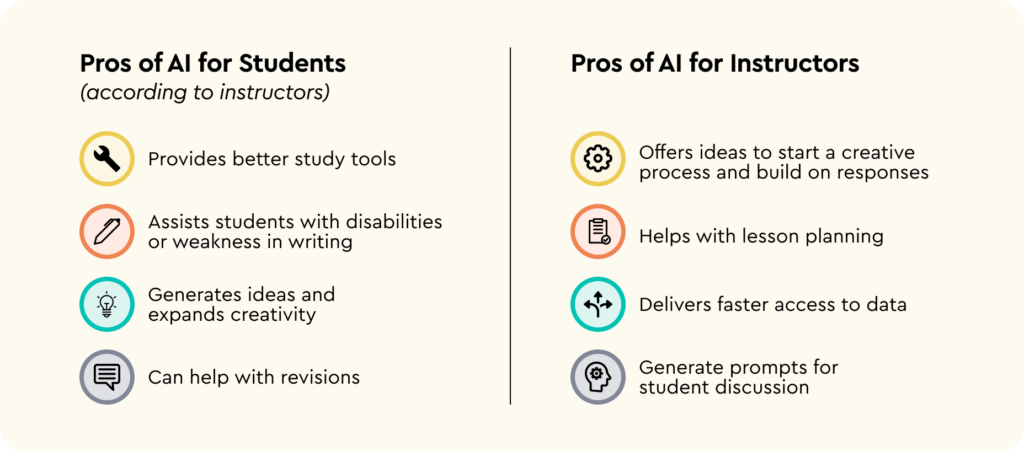

Mollick has started using AI as a kind of virtual sounding board or brainstorming tool, where students ask ChatGPT to generate ideas for class projects and then scrutinize those results with group discussions and further AI prompts. “And the ideas so far are great, partially as a result of that set of interactions,” says Mollick.

This demonstrates one way professors are organically developing more authentic assessment methods that work within the new AI-saturated environment. Simply outlawing the use of AI tools, as NYU has, may sound like solidarity with all things human, but the reality is the role of human educators and administrators is changing. Bert Verhoeven, an educator at Flinders University in Australia has also joined the group of professors who require the use of AI for all students. Verhoeven sees creators and educators now as co-pilots or co-creators, who use AI tools for idea generation, and gain insight through repeated feedback loops and narrowing down instructions to cycle back into the AI content generator.

Students who are tempted to use AI to write complete essays or provide answers to exam questions may be interested to know that as far as high-level learning is concerned, AI may not be ready for prime time. One Wharton professor recently fed the final exam questions for a core MBA course into ChatGPT and found that the results displayed some “surprising math errors” (though the final grade would likely have been a B or B-).

Vice shares the experience of David Levene, Chair of the Department of Classics at NYU, who ran various essay prompts through ChatGPT, and reported that the essays it came up with were “at best B- standard, and at worst a clear F.” Certainly this grading result may display some anti-AI bias, since Professor Levene was fully aware that the essays he was evaluating were created using the AI tool, but anyone who has spent significant time reading AI-generated content will likely agree that it is often poorly written and rife with errors.

Rather than banning AI tools or using unreliable AI-detectors, educators may find more value in combining AI’s capabilities with more personally interactive, collaborative assignments incorporating authentic assessment and feedback techniques.

Educator, author and consultant Derek Bruff, Ph.D believes that there’s greater and long-term benefits to students by teaching with AI tools.

One growing solution is utilizing video-based assessment software to design authentic assessments that provide learners with enhanced opportunities for practice, demonstration, and feedback through video.

Video evidence is a powerful tool that provides authenticity and evidence of what you don’t know you don’t know:

It’s clear that secondary and tertiary education is in need of a more effective, resource-conscious approach to student assessments in today’s digital, AI-saturated world. Educators and students must commit to new assessment technologies and strategies that enable more meaningful skill development, classroom evaluation, and preparation for real-world interaction and success.